The Game-Changing Secret That Will Make Your Band Sound Better

- By Jason Brown

- 45 Comments

It’s the middle of rehearsal, and the music is sounding, um—chaotic… loud… just all-around muddy, and… you have no clue what to do to fix it! Ever been there? Have you found yourself asking… “How come my musicians sound fine when they play on their own, but they sound messy when they play together?”

Join the club! The good news is: there’s a surprisingly simple—but radically effective—principle you can apply that’s guaranteed to make your team sound a whole lot better. Sound too good to be true? Trust me—it’s not… so let’s dive in!

They need to play less.

Wait… what? Sound counterintuitive? But truly—this is the thing that will make all the difference in the world… when musicians know how to leave more space and how to hold back. It doesn’t mean they CAN’T play complex, intricate stuff, and it certainly doesn’t mean they DON’T ever do that… but they know the right time and place for it, and they hold back the rest of the time.

French composer Claude Debussy famously stated:

“Music is the space between the notes.”

Pause and think about that—beautiful music is not just the notes that are being played… it’s the artful arrangement of breathing room, pauses and dynamics AMONGST the notes. When musicians do this effectively, a song goes way beyond just mere melodies—it becomes an emotional journey for the listener.

Now, this principle of playing less isn’t a cure for poor musicianship. If people are playing wrong chords or playing out-of-tune instruments, or they can’t stay in time with a metronome—those are separate issues, and they absolutely need to be addressed, but that’s not what we’re talking about here!

What we’re talking about is why reasonably-skilled musicians don’t automatically sound good when you put them together. They’re all talented individuals… they all sound good on their own, and logically, you’d think they would sound great when you put them together… but they don’t. Why? Because knowing how to play with a band is not the same as knowing how to play your individual instrument.

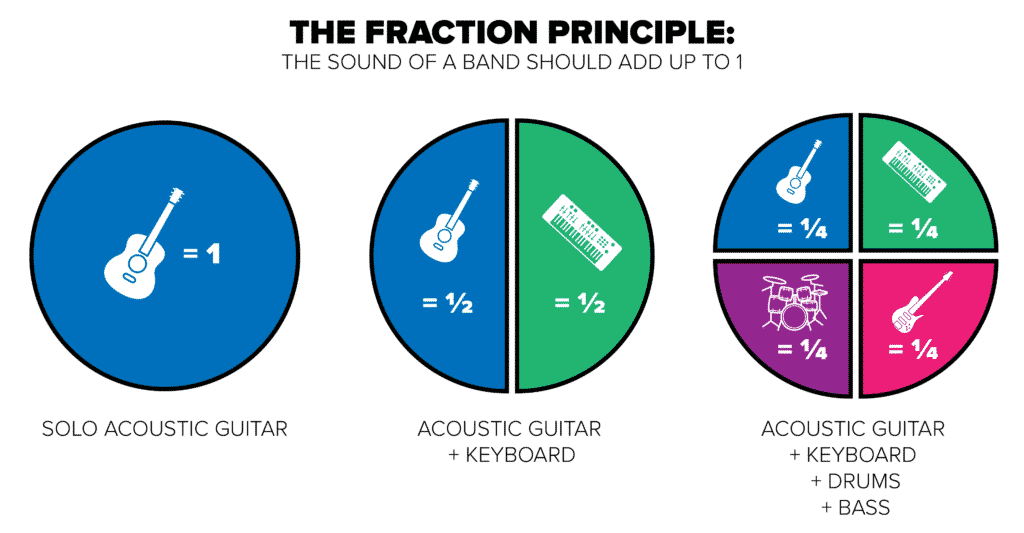

The Fraction Principle

I promise you… this will CHANGE. THE. GAME. for your band if you put it into practice.

The Fraction Principle states that the sound of a band should add up to 1. Meaning, if I’m playing my acoustic guitar on my own, my sound adds up to 1—it’s the whole “pie.” But… if I’m playing with a keyboardist, we both need to back off a bit and play less than if we were on our own—we split that pie into two and each get half. If we add a drummer and a bassist, that pie is now split into 4, and each of us is playing 1/4 of what we could play if we were on our own.

Anything adding up to more than 1 doesn’t work in a band setting… that’s where the instruments start stepping on each other’s toes and the sound gets messy. If all 4 musicians are playing full out, it adds up to 4 instead of 1… and the result sounds cluttered and muddy!

Put that into your own worship team context. The smaller the team, the more “weight” and responsibility each player has (a bigger piece of the pie). The larger the team, the more essential it is for each individual player to hold back and restrain their contribution—in order for all the parts to fit together.

The result?

No more clutter. No more messy, muddy sound.

The beauty of each individual instrument starts to shine through, instead of everything being hidden in the chaos.

The challenge of classical training

Musicians (usually keyboardists) who come from a classical background can find the concept of “playing less” particularly difficult—they are accustomed to being a solo instrument playing the whole time and filling up ALL the available sound (ie ME = the whole pie). But even though they might be a maestro in that context, that type of playing doesn’t fit in a worship team setting—here, less is more.

It might even feel “beneath them” to play simple chords or motifs when they have the chops to play beautifully complex parts instead. And the truth is—yes… it is beneath their skill level… but that’s ok! Same for a vocalist—just because they CAN do fancy licks and trills and sing up into the stratosphere… doesn’t mean they SHOULD. The question we all have to ask ourselves is… are we on the team to showcase our chops, or are we submitting our part for the greater benefit of the team?

So how does this actually work?

Let’s make this practical. I can’t play my acoustic guitar the same in a Sunday morning band context as I would if I was leading a small group and playing alone. For the small group, it would require lots of rhythm, strumming, momentum and presence from my guitar… but in a band, much of the rhythm would come from the drums, and the keyboard is likely providing most of the foundational chords. I’d need to play less, and play differently, in order to fit in that context.

“What about the other instruments in the band?” you say… “How do I apply the Fraction Principle with my team?” Here are some specific ideas (and “language”) that you can use to communicate this concept with your musicians!

- An acoustic guitarist shouldn’t strum all the time—they should stick to simpler downstrokes, occasional strumming, light finger picking, etc.

- A keyboardist shouldn’t play as heavily (or maybe at all) with their left hand when a bass guitar is also playing those low notes.

- The placement of the keyboardist’s right hand should move higher or lower to contrast the other instruments carrying that section. For example, if the acoustic guitar is carrying a section of the song in standard, open tunings (ie mostly mid-range notes and chords), the right hand of the keyboardist might move higher; if the electric guitar is leading out with lots of high notes, the right hand of the keyboardist might move lower.

- Electric guitarists shouldn’t strum chords the same as the acoustic guitarist, nor should they belt out riffs all the time.

- A bassist shouldn’t play busy melodies and licks all the time, if ever—they should embrace consistent, repetitive patterns that lock in tightly with the drums.

- A drummer shouldn’t do fills and intricate rhythms all the time—just like the bassist, they should embrace consistent, repetitive patterns to which the rest of the band can lock in tightly. Nor should they constantly use their hi-hats or cymbals to keep tempo—instead, they could spend a section of a song just using the toms and snare, or look for other ways to vary the specific drums/cymbals they’re using as the song progresses. Especially if your team uses a metronome in their in-ears, the drummer doesn’t also need to provide constant tempo.

- Lead lines and decorative melody parts should rarely be played by multiple instruments simultaneously. For example, if the keyboardist is playing the intro for one song, then the electric guitar should probably back off—and vice versa, for another song, if the electric guitar is playing the riff, then the keyboardist should play simple background chords.

- Every musician should identify the place(s) in the song where they will need to be at their fullest or loudest, and work backwards from there to reduce or restrain themselves the rest of the time. For example, the drummer might identify the final bridge repeat into chorus as the place to go full-out with his crash cymbals and driving rock groove. Subsequently, he might decide not to ride those crash cymbals anywhere else in the song so that he has that final level of intensity available for that final bridge and chorus. A keyboardist might identify that same final bridge repeat as their biggest moment—and subsequently make sure to start the song (first verse & chorus) playing simple sustained chords (ie NO extra rhythm/groove/embellishment) to leave lots of room to grow to that point.

Bottom line: there should be a constant give-and-take of certain instruments carrying the weight of the sound at any given moment, while the others play more simply or sit out altogether.

“What can we take away?”

This is the most important question you can ask when aiming to apply the Fraction Principle and clean up muddy sound. Instruments that are doubling up on each other’s parts is an easy place to start. No two acoustic guitars should be playing the same thing—instead, encourage your guitarists to utilize capos or different chord shapes, or to alternate finger picking and strumming. This goes for electric guitars too—there should be variety amongst the rhythmic strumming, lead lines, chord placements and effects being used.

One of the greatest impacts a musician can make to the sound of the team, however, is…

Don’t play at all.

No, I don’t mean for the whole time—I mean, be ok with sitting out for an entire section of a song (like a verse, or the first half of the bridge, etc.).

Sonically, when people’s ears listen to a set of frequencies for too long, they become accustomed and “dull” to those frequencies, so if you’ve been playing for awhile already, the sound of your instrument has actually lost its impact to their ears. But… when you pull back and stop playing entirely, their ears notice that change in frequency and they “reset” to the new combination of instruments. Then, you can resume playing (even after just a few phrases!) and it’s “new” to their ears again!

Take note though—that impact is nowhere near as powerful if you simply back off your playing from 100% to 50%, or even to 10%… trust me… sitting out entirely is the MOST impactful contribution you can make to the dynamics of a song.

Ideally, throughout a song and definitely throughout a worship set, each instrument should find appropriate places to sit out entirely while the rest of the instruments play, and then strategically come back in at a moment where the dynamics need a boost. (Drums, I’m especially looking at you—as a drummer myself, I know just how strong the tendency is to keep playing the whole time… but that sabotages our ability to make a greater impact on the dynamics of the song and worship set!)

It’s a hard truth, but an important one:

Just because you’re on stage and holding an instrument doesn’t mean you should be playing all the time.

It’s not “weak” or “lesser” of you to stop playing—in fact, it’s actually the stronger, better choice.

So find those moments… just put your hands down (or raise them!) and get really comfortable doing that (no matter how awkward it feels at first!). 😳

To sum up…

The most important principle you can apply to musicians on any band is to treat the sound like a whole pie, and divide that pie up amongst all the players… each playing a fraction of what they could if they were playing on their own. Ask the question, “What can we take away?” and look for ways to create a “give-and-take”… an ebb and flow of instruments being more present and less present throughout each song.

Most importantly, look for places where an instrument can sit out entirely, so that when they resume playing, they bring a noticeable sonic change and boost to the dynamics.

If you’re a musician on the team, I encourage you to take initiative and start doing this. If you’re a worship pastor (or if you have “say” at rehearsal!)—lay this out for your team… and remember… CLEAR IS KIND. Don’t just “float” vague ideas of what to do. Be specific. Be strategic. Listen to the songs on the set list intently and pay attention to what the instruments are doing, so you can be prepared to give direction to your musicians. And be sure to let them know the WHY behind it!

Try it out at your next rehearsal and let me know—how did it go? What changes did you notice to the sound or dynamics? What other ideas would you give to a worship band wanting to sound better?

Responses

So good! Thanks for sharing!!

You’re welcome! Glad it was a help!

This is *fantastic* and so timely. I was just speaking with fellow musicians about how playing individually and playing in a band is not the same, and how I wished there were teachers/helpful guides to teach that kind of stuff. And the next day, I received your post. It was so clear and practical. Thank you!!

Wow! Thanks Brittney! Glad this was so helpful, and timely too!

Really solid advice here, communicated in simplistic terms.

Less is Always more! Thank you so much.

Thanks Melody! Glad it was a help!

Really great info conveyed in exceptional way. We are blessed to have most of our musicians play together in the way that you have described.

Thanks Dorinne! What a blessing!

Thanks Jason, I have a new drummer and he is playing so many fills, that we do not have an actual drum beat. I’m a drummer myself, so this will help me immensely!!

Oh man, I feel the struggle! So glad this is helpful Randy!